Breaching Dammed Legacies

written by Kamna Shastri

cover illustration by Rae Lee

Article Sections

opening

Part 1: The Problem

Part 2: The Politics

Part 3: The Possibility

If you are in Washington, you likely fill in your ballot with a ballpoint pen, slip it into its envelope and either send it off into the mail or find your nearest dropbox to have your vote counted.

Salmon runs are an integral part of the ecological cycles of the Pacific Northwest. The dead carcasses of adult salmon that line river beds and shores after spawning season provide important nutrients to the forests, enriching the soil and sustaining the wildlife that share this land.

Southern Resident orcas rely on Chinook salmon, which are integral to their diet. With little food to feed them, these endangered species struggle to produce offspring. Even when they do, calves face the odds of malnourishment and starvation.

Salmon are our keystone species. When they suffer, the effects cascade like falling dominoes.

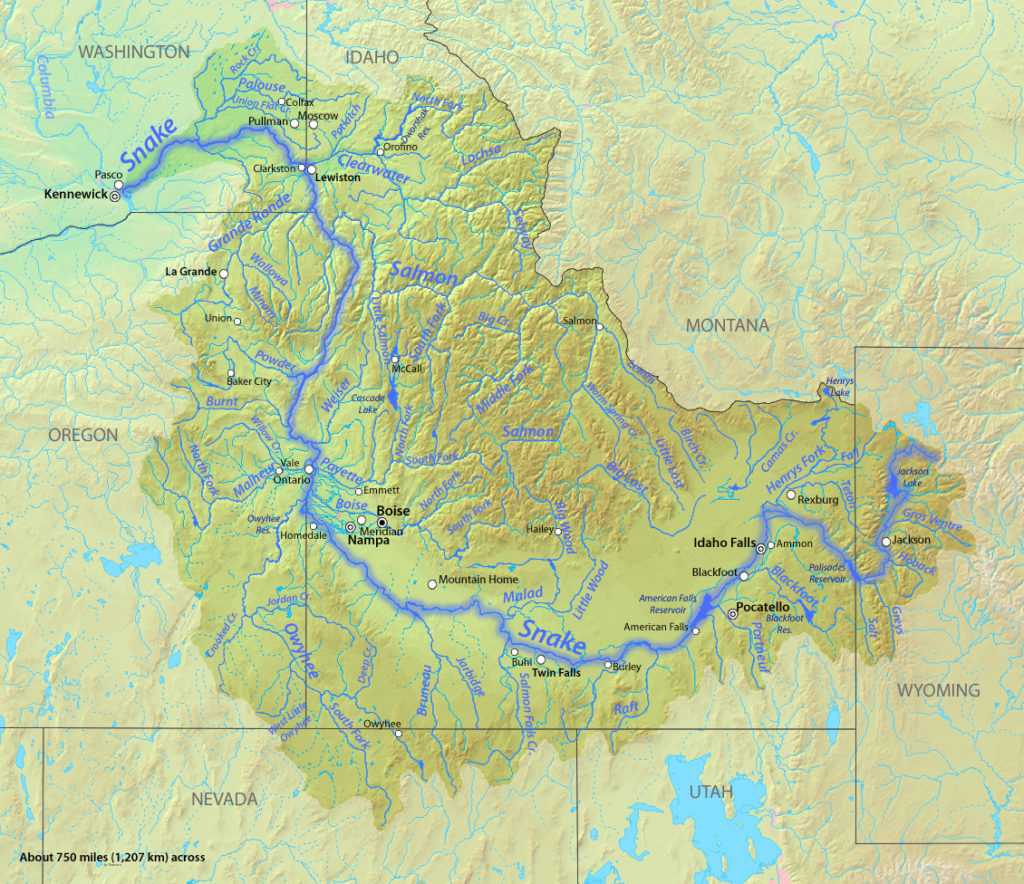

With dwindling salmon resources in our state, the Snake River has become a crucial area to concentrate efforts to revitalize our state’s salmon population. A history of overfishing, damming, and stagnant reservoirs have impacted salmon resilience.

In this corner of the world, we are only as strong as our salmon runs. They are the compass needle swinging between two futures: one where climate change results in incalculable loss and one where we can build towards resilience.

Stop Salmon Extinction – Free Snake River Rally

Rally with music, speakers, give-away, and snacks. Then a procession with puppets, signs and costumes to the Congressional Offices.

3/26/2022, UW Tacoma:

4/2/2022, The Olympia Ballroom:

Part 1: The Problem

Since the four Lower Snake River dams were built in the 1960’s, wild Snake River chinook and sockeye runs have decreased by 60%. A study by the Northwest Energy Coalition cites a 90% decline in overall salmon runs because of the dams.

This summer, temperatures soared into the hundreds, broiling river waters that were warmer than they should have been. Hundreds of salmon died. Some began developing a sinister fungus caused by unwelcome temperatures. Extreme heat events like these are increasing and will only become more common as the earth warms from climate change.

But the temperature of the Snake River waters had already been heating up. That is what happens when a river has a dammed legacy. Dams, and accompanying reservoirs, disturb the natural flow of a river, creating segments of water that collect and retain heat by remaining stagnant or slow moving. The temperature of the Snake River is beyond a safe threshold for endangered salmon.

The US Army Corps of Engineers Walla Walla District owns and operates the four Lower Snake River dams. Online, they tout their efforts to make fish passage easier, through ladders, cooling systems, spill operations, and surface level passage. The agency says “these improvements are making a positive impact on salmon and steelhead returns.”

In 2020 the Army Corps of Engineers and partners conducted an environmental impact assessment of infrastructure in the Columbia River Basin and came to the same conclusion many advocates had been pushing for. Salmon were not doing well. Additionally, these dams were no longer cost effective. They produced less energy with sinking profit margins that made maintenance and upkeep of the infrastructure cost more than the revenues amassed by the dam’s operations.

Snake River Dams Dinner Hour

The world’s most exciting river restoration effort is at our fingertips, right in your backyard. Tune in to our Snake River Dinner Hour webinar series to hear how we’re going to stop salmon extinction.

The electricity generated by the dams and distributed by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) since the early 1940’s now costs more than renewable energy sources like solar and wind. BPA is also undergoing its own financial strain as renewable energy sources increasingly come into the energy market and the surplus electricity they once sold to California has lost value as California fortifies its own local energy grids.

Removing the dams makes financial sense, and would open up 70% of the Snake River salmon’s natural habitat making it the largest salmon restoration project ever undertaken.

Beyond the hydropower industry the Snake River dams are also conduits of economic growth and cooperation. Growers and farmers are dependent on irrigation from the dams to grow crops that support their livelihoods; and the shipping industry relies on the dams for locks that allow for barges to transport goods between Idaho and Washington.

These industries have relied heavily on the river’s dammed status. Dismantling the dams, especially without an alternative solution to replace the services provided by the dammed river, feels like a risky change. Yet there is an increasing consciousness across industries that the full functioning of the river ecosystem is necessary to support the longevity of farming, outdoor recreation, and a future for their communities.

A recent Seattle Times headline reports some irrigators in the Lower Snake Rivers support drawing down two of the dams in light of disappearing salmon. The article quotes Dewey Holliday, president of the irrigators association, who recognizes integral aspects of rural life are at stake without a solution for salmon health.

“I’ve earned my living most of my life from agriculture. I love fly-fishing for steelhead on the Grande Ronde River in Eastern Washington, and I want my grandkids to be able to do that, and I want to be sure my kids and grandkids will be able to farm, too,” Holliday said to the Times.

Meanwhile in Idaho, outdoor recreation and fishing industries have taken a financial hit due to salmon and steelhead populations. An article from the National Resources Defense Council details how the state’s communities have faced million dollar losses; the Nez Perce and Clearwater counties generally receive over 8.5 million dollars in revenue from steelhead fishing. However, this past September all fishing was closed on the Clearwater River, and limits on fishing were imposed on the Snake and Salmon rivers. The losses from these restrictions have business owners deeply worried.

“…there is an increasing

consciousness across industries that the full functioning of the river ecosystem is necessary to support the longevity of farming, outdoors recreation, and a future for their communities.”

Part 2: The Politics

In early 2021, Idaho Congressman Mike Simpson, a Republican and an avid fisherman, proposed a plan and accompanying budget to aid salmon restoration on the Snake River after convening over 300 meetings with stakeholders during the course of several years to better understand the situation. This 33.5 billion dollar implementation fund would go toward dam removal, recreation, energy and transportation solutions, honoring Tribal treaty rights, to transform the Snake River that works for both people and salmon. Years before, Simpson said “You cannot address the salmon issue without addressing dams…they are interwoven,” during a lunchtime event in the spring of 2019.

This year, Washington governor Jay Inslee made clear that Snake River dams is an important state-wide issue and that a comprehensive plan was necessary to move forward. In October, Inslee, and Senator Murray jointly announced next steps for a joint federal-state process on salmon recovery in the Columbia River Basin and the Pacific Northwest. They intend to conclude their stakeholder engagement and consultation with the tribes, and release their recommendations no later than July 31, 2022. This initiative will analyze the replacement of services provided by the lower Snake River dams.

There is evidence that services provided by the dams can be recouped in new ways that bring more opportunities to the community, while also considering the health of our environment and ecosystems. According to a 2018 study by the Northwest Energy Coalition, the lower Snake River dams only provide 4% of Washington’s electricity. Their study found that the energy generated by the dams can be replaced through a “balanced portfolio” of new wind, solar, and “demand-side resources” which include energy efficiency and energy storage. Not only is this feasible, but it could happen in a relatively short timeline – 10 years – and would aid a regional drop in greenhouse gas emissions.

At WEC, our involvement officially began in October 2020, and our intent has been to act as a support, building power together, and adding value where needed with those leaders who have been at the helm of the fight to remove the Snake River dams long before we got involved. Many organizations and tribes have already been in this fight for decades. Similar to the successful dam removal efforts on the Elwha River and the White Salmon River, it will take time, a public upswell of support, and a unified voice.

Russell Hepfer, a Lower Elwha Klallam councilmember, looks out over the restored Elwha River Estuary.

“We are the Klallam People”

“The dams have outlived their benefit”

“It’s kind of like a business deal”

Part 3: The Possibility

Russell Hepfer stands looking out at the mouth of the Elwha River where freshwater and saltwater from the strait of Juan de Fuca meet. A seal bobs up and down, its dark head peeking through the gray water to reach for a passing seagull. “Hey!’ Hepfer calls out to shoo away the predator, his voice cutting through the quiet gray afternoon.

From this point on the Northern edge of the Olympic Peninsula and five miles inland, Hepfer explained, was the Elwha dam, built in 1910. About seven miles more from that point stood the Glines Canyon dam, which began operation in 1927. Together these dams held back so much sediment that the river spilled out onto ancient shores, turning them into watery depths.

Once a commercial diver, Hepfer had plunged into those waters “and we would dive for sea urchins in 20-30 feet of water off the mouth of the Elwha,” he said. “And now, where I was diving, you can stand on land.”

Removing dams is not a novel idea. The Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, all of 1,000 people, managed to remove the Elwha dams after over twenty years of planning and negotiations. Their treaty rights had been violated as salmon populations dwindled and they stood to lose not only their beloved salmon, but their sense of identity and connection to their ancestors — priceless resources that monetary value cannot capture.

More clips from our conversation with Russell

“There is money”

“Most of the credit goes to the people who are gone”

“This put truth to all of the legends and stories that were told to us”

Totem Pole Journey

This Summer, the House of Tears Carvers of the Lummi Nation will transport a 25-foot totem pole from Washington State to Washington DC, stopping with communities leading efforts to protect sacred places under threat from resource extraction and industrial development.

The dams had stolen over 120 acres of land from the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, in addition to all the ancestral lands that had been ceded to the US government through treaties. Dams had also devastated salmon runs. Hepfer remembers that in his youth, you could catch 100 fish a day. Now a good day means catching maybe 18. Usually the catch is even less.

It took over twenty five years to get to the day when deconstruction began in September, 2011. The Lower Elwha Klallam tribe led this fight, and had a lot at stake, yet they worked to breach the dams with a number of different government and industry partners. Navigating federal and state regulation and resource agencies added to the decades-long process. And much like the current Snake River controversy, not everyone was on board.

Getting to an agreement with various community and industry stakeholders took many meetings and what began as a 100 million dollar project to remove the dams tripled by the time an agreement was reached. People are so afraid of change, Hepfer says, that it was hard to imagine a future without the dams. All the players weren’t always happy, but they did have to agree on how to move forward.

The undertaking brought economic benefit to Port Angeles as much as it rejuvenated the ecosystem. Construction jobs brought people into town. Biologists and scientists were needed. People had to find living arrangements which injected the community with money.

When the dams came down, salmon began to return almost immediately, swimming through Indian Creek which runs between the two dismantled dam sites. The fish would be tagged so that scientists could track their routes. By September 2013, steelhead had returned, and sockeye would soon follow. The river ecosystem began to take up its rightful space without obstruction.

As the river reclaims its shape, the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe has also been able to reclaim traditions and stories that had been lost for over one hundred years. Hepfer shares that, when the waters receded, a sacred site bearing the markers mentioned in their creation story was uncovered.

Fishing is still not allowed in the river as it recovers and heals from one hundred years of changing course. The long and arduous effort to remove the dams is a source of pride and great affirmation for the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe, and for Hepfer. “We’re salmon people,” he says. “If you treat salmon well, they will come back. It took us 100 years to do that. But they’re coming back.”

The story of the Elwha and the Snake rivers are not the same, though there are parallels. There are many interests and considerations to balance between different players who are tied to the river and the dams. Each has a unique intersectional history with the land and with the benefits or drawbacks of our current economic system. While communities around the Snake River — including Native Nations, industry, and the agricultural sector — will have to find a solution that works for them, the Elwha is a reminder that salmon can and will return and that rivers have an intelligence and ability to re-calibrate if given a fair chance.

Salmon are the axis of our ecosystems and our Pacific Northwest culture; if they aren’t doing well, neither is our land or our people. Solutions come in many forms and removing the Snake River dams is one of them. How we will choose to work together and harmonize a solution that benefits our rivers, our fish, and our rural communities will decide Washington’s future now and for generations to come.

Join us 3/26 for the Rally & March to show public support for Snake River salmon, honoring tribal treaty rights, and solutions that support all the communities

Tune in to our Snake River Dinner Hour to hear how we’re going to stop salmon extinction

Your tax-deductible donation ensures a sustainable future.