How did we come to a place where the great outdoors is seen as “white space,” or where most large environmental organizations are run by white people and mostly staffed by white people? It’s the legacy of white supremacy, a system that hurts us all and depends upon the widespread erasure of the contributions of Black Americans. It’s one of the many reasons that February was established as Black History Month. This dynamic is something that we grapple with at Washington Conservation Action, and work to undo, both internally and in the larger world. This is not work that is ever “finished.” Remembrance and acknowledgment will always be an essential part of it.

It bears repeating that there have always been, and continue to be, Black Americans inspired by nature and motivated to fight for it. Here are some local conservation champions you should know, and some historical figures to remember during this month and every month as we lift up Black stories and achievements:

Ray Williams founded and directs the Black Farmers Collective which operates two urban farms, one literally greening a right-of-way off I-5 near downtown Seattle. Williams and his team started working Yes Farm in Yesler Terrace three years ago. Williams seeks to build a Black-led food system, an education space and an oasis that fosters healing and joy in the BIPOC community. The collective is developing a four-acre plot, Small Axe Farm, near Woodinville that will be a place for training aspiring Black farmers.

“What we eat is a major factor in our future health. Creating a diverse, resilient local food system is part of our community’s mitigation of climate change,” Williams told the Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. “By reframing the notion that farming and working the land is ‘slave work’ to acknowledge it as an act of building and feeding the nation; by uncovering great contributions of African American research to farming techniques; and fostering Black land ownership will help heal some of the wounds of the past.”

Savannah Smith and Ebony Wellborn met in 2019, while working at an environmental non-profit as part of Americorps. During a visioning exercise toward the end of this program, they realized that what they wanted to do most of all was to create opportunities for BIPOC youth to be exposed to marine ecosystems and to find opportunities in the maritime industry. They have since founded Sea Potential, a company that works toward those goals. They work on two tracks: 1) creating programs that help BIPOC youth learn more about the sea and develop positive associations with it; and 2) Working with maritime companies to help them be more inclusive in management and hiring.

Chelsea Murphy founded She Colors Nature after moving to Leavenworth. She fell in love with outdoor mountain activities, but quickly realized how non-inclusive those spaces tend to be. For instance, just 23% of National Park visitors are people of color, despite being 42% of the U.S. population, according to a 2020 survey. The mother of two, with a third expected in March 2023, Murphy works to promote a more inclusive outdoor community through advocacy, a blog, and a film, Expedition Reclamation, that highlights Black, Indigenous women of color as they connect to nature in various ways.

Bennetta Robinson co-chairs the Seattle Environmental Justice Committee. She believes that “equitable climate solutions will make the difference between good cities and great cities.” Currently a senior researcher for Renewable Energy Organizing at the AFL-CIO, she has studied the effects of abandoned oil and gas wells in communities of color along “Cancer Alley” on the Gulf Coast. She has modeled the impacts of natural disasters on vulnerable populations and documented the challenges of collective bargaining in the southern United States.

Black Conservationists to Know

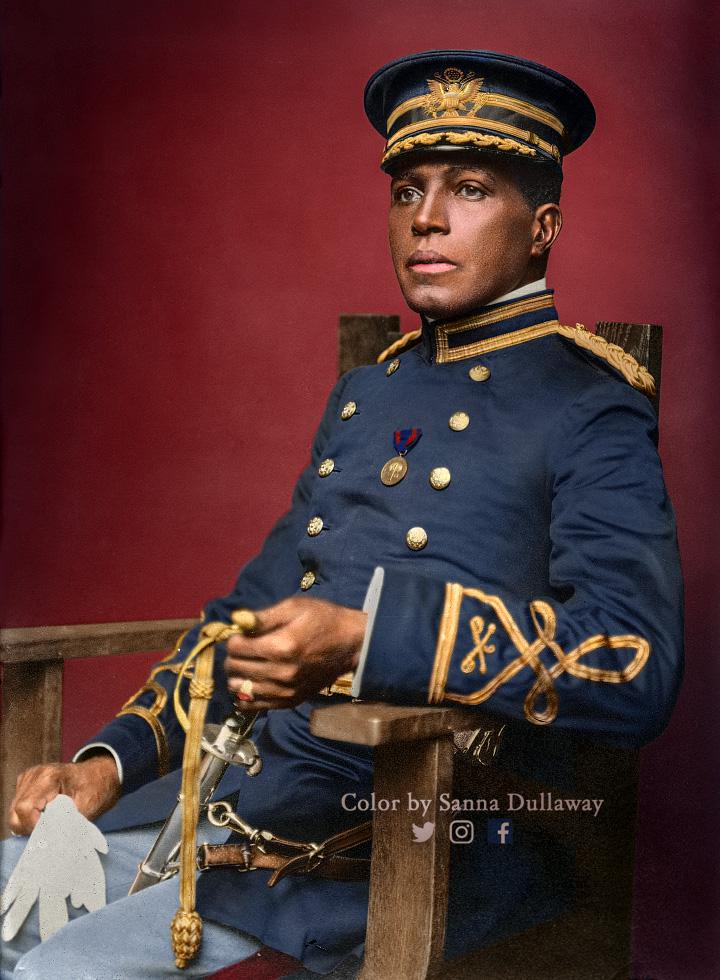

Col. Charles Young (1864-1922) was born into slavery in Kentucky in 1864. After Emancipation, he went on to become highest-ranked Black officer in the US military during his time. In 1903, he became the Superintendent of Sequoia National Park in California. He oversaw the development of many hiking trails still in use today, as well as convincing many private landowners bordering the park to sign over their land. This strategy for expanding national parks became a national standard.

Learn more about Col. Charles Young here

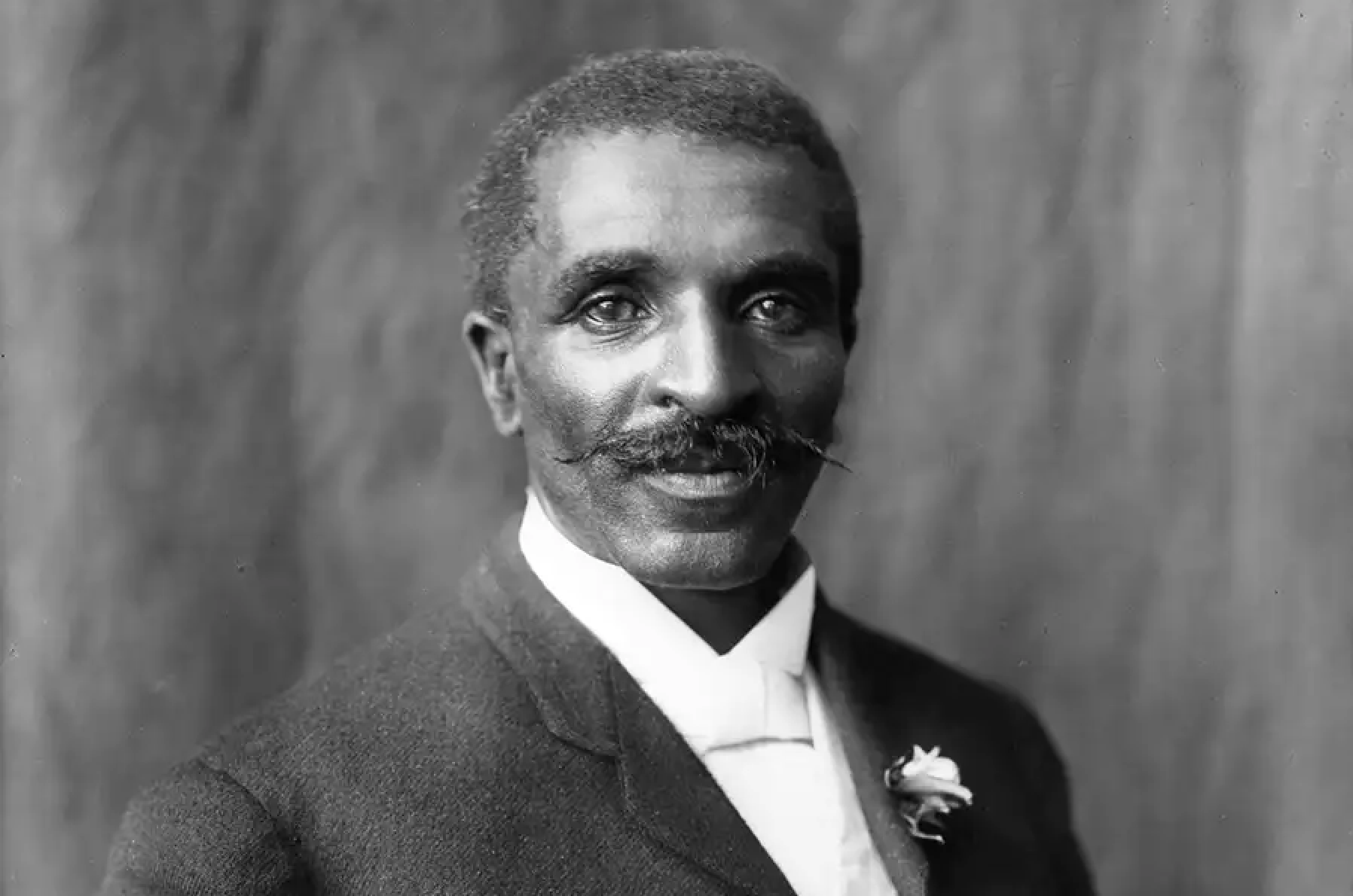

George Washington Carver (1864-1943) was one of America’s most brilliant agricultural researchers and educators. He developed innovations in crop rotation that helped to preserve soil while increasing productivity. A deeply spiritual man, Carver believed that everything is deeply connected, and that ignoring that reality creates devastating problems.

Hazel Johnson (1935-2011) began investigating high cancer rates in her Chicago neighborhood, a housing project on the southeast side of the city near the Indiana border. She discovered the problem was environmental. The housing project, Altgeld Gardens, was built on the former toxic dump site of the Pullman Rail Company. It bordered the Calumet industrial area, bounded by abandoned factories, a sewage plant and a freeway that created polluted air, water and land. Johnson founded People for Community Recovery in 1979. This organization sought to increase environmental awareness, and to draw attention to the disproportionate burden of pollution on low-income, BIPOC communities. Johnson was one of the first to popularize the concept of “environmental racism.” In 1994, she helped to inspire President Bill Clinton to sign the Executive Order that directs federal agencies to consider the health and environmental harm their actions may cause to overburdened communities.

Working as an environmental sociologist, Robert Bullard (1946- )in the late 1970s documented the systematic placing of garbage dumps in Black neighborhoods. Many consider his book, Dumping in Dixie, to be the first to fully articulate the concept of environmental injustice.

A serious 1971 oil spill in the San Francisco Bay deeply affected John Francis (1946- ) In response, he decided to give up all motorized transit hoping to inspire others to rethink the oil economy. For 22 years, he walked everywhere, including treks across the United States and through large parts of South America. He often found himself arguing with others about his decision. One day, he decided to stop talking, to listen to others. That led to 17 years of silence. Francis became known as the “Planet Walker.” The United Nations Environment Programme named him a Goodwill Ambassador in 1991

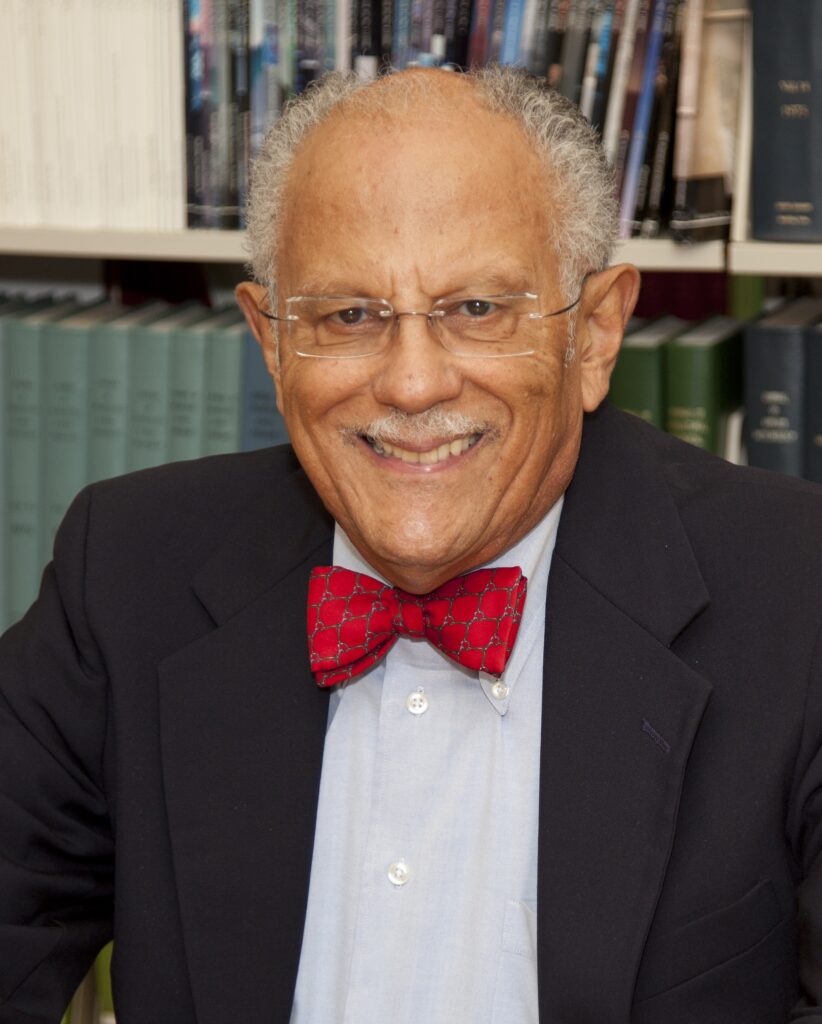

Portland, Oregon native Dr. Warren Washington (1936- ) in the 1960s helped to develop ground-breaking atmospheric computer models. His models have become a standard in climate and weather science and are still used to help predict how the climate may change in the future. He shared in the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his work with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Hattie Carthan (1900-1984) decided to take action in the 1960s when her Brooklyn neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant began to fall on hard times, with buildings falling into disrepair and street trees dying. At first, she just started spreading tree seeds. But eventually, she formed a non-profit that created a community garden and planted more than 1,500 trees. She is considered one of the first to “regreen” a community. Her legacy lives on in a youth education program and community gardens that still thrive in Brooklyn.