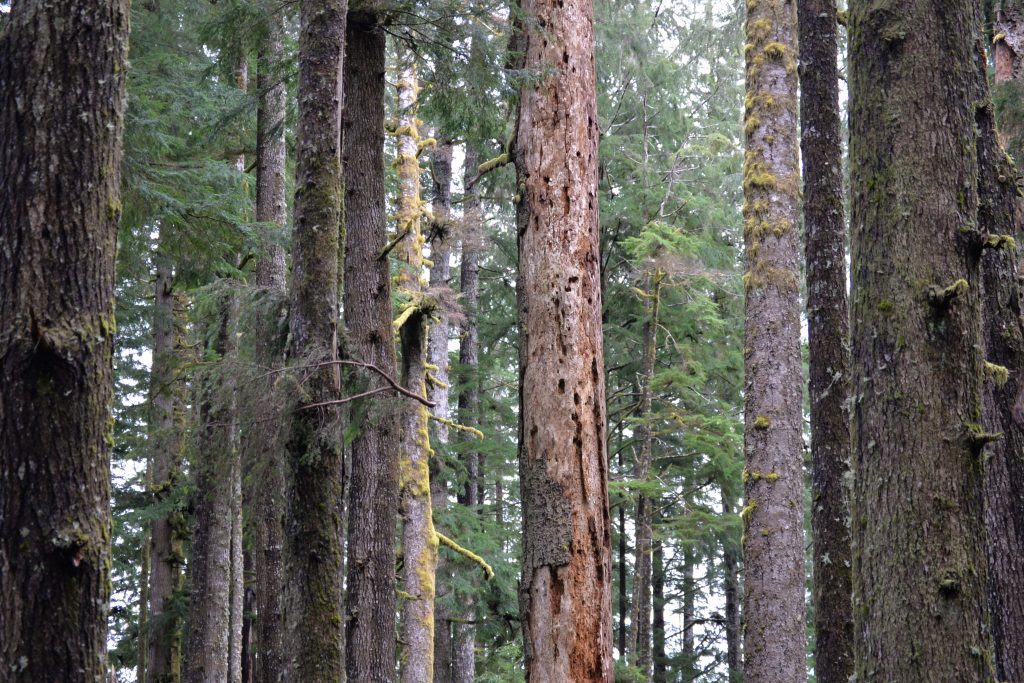

I was on Reade Hill Trail just outside of Forks, Washington. Managed by the Department of Natural Resources (DNR), the trail serves an educational function as well as a recreational one as part of the Olympic Experimental State Forest (OESF). A windstorm knocked over the forest in 1921, and it was allowed to regenerate naturally. After almost one hundred years of being ‘unmanaged,’ the trees had developed old growth characteristics—trunks and branches furred over with moss, the lower canopy mostly withered away, eliminating a feeling of claustrophobia that the younger section of forest induced.

Achieving the right balance between generating money from tree harvest and setting them aside for conservation is complex, and no one expects this to be easy.

The OESF is faced with a challenge—it must attempt to fulfill two traditionally opposing goals. DNR states, “The primary working hypothesis for the OESF is that it is possible to manage a working forest for both revenue production and ecological values.” Achieving the right balance between generating money from tree harvest and setting them aside for conservation is complex, and no one expects this to be easy. In fact, DNR is partnering with the University of Washington to do extensive research and monitoring in the OESF to find that balance.

Decadent Forests

The DNR established the OESF during a time when policy surrounding forest management was radically shifting. Until 1988, DNR’s policy was to harvest the oldest trees first; that made sense from an economic perspective—the oldest trees generated the most revenue. Why harvest ten trees when you can get the same amount of board feet from one, gigantic old tree?

Additionally, the forest of the Pacific Northwest had long been seen as an infinite resource. Asa Mercer, an early settler in Seattle, wrote, “The supply of logs for lumber will only be exhausted when the mountains and the valley surrounding the Sound are destroyed by some great calamity of nature. For when this generation shall have perished, the forests by them laid low will have begun anew to assume proportions that do honor the former growth.” This mentality encouraged unmitigated and reckless harvest of forests for decades.

However, in 1891, alarmed by the increased rate of harvest allowed by advances in technology, the government passed the Forests Reserve Act to ensure a steady supply of logs to a timber-hungry country. Millions of acres were set aside to be managed by the US Forest Service. But our national forests were meant to produce timber in perpetuity, not for environmental conservation. In the early days of the US Forest Service, the prevailing ideology was that old growth forests were over-ripe; enormous trees that had reached the pinnacle of their life span and were naturally hollowed out from rot were often regarded as “decadent,” as in a decaying or deteriorating state. The US Forest Service then began to turn America’s national forests into densely grown, homogenous, and frequently harvested tree farms, an idea soon embraced by the timber industry. This principle of sustained-yield forestry guided the agency until the 1980’s. Washington’s DNR was operating under similar principles.

Only about ten per cent of the historic range of old growth remains and most of those forests are on state and federal lands.

But in 1988, DNR came to the startling realization that the agency was on track to cut nearly all of the last remaining old growth forests on DNR land within the next fifteen years. Approximately 60,000 acres of old growth would be gone on the Olympic peninsula alone, and as a result, timber production would dwindle causing a collapse in revenue. They would have to wait until 2030 for the second growth to catch up to similar harvest levels. DNR had harvested too aggressively for too long. Today, almost all of the remaining old growth in the United States has been harvested. Only about ten per cent of the historic range of old growth remains and most of those forests are on state and federal lands. The glib predictions about inexhaustible forests made by Asa Mercer were wrong.

Rise of Environmentalism

Aside from concerns about future harvest projections, DNR would have to comply with the Endangered Species Act. In 1990, the northern spotted owl went on the endangered species list and forced the state to preserve their old growth habitat. This came at the expense of rural communities already hemorrhaging timber jobs due to mechanization and a growing market for logs in Asian mills.

Research began to show that downed wood was essential to the health of the forest.

The culture also shifted. Concerns about the fate of old growth forests were spurred in part by the sudden spike of hikers, and environmental non-profits (like WEC) began to agitate for preservation. Science also began to push back on the notion that old growth forests were rotten or biologically barren. Research began to show that downed wood was essential to the health of the forest. For example, snags and rotting logs provide habitat for a wide range of species both boreal, terrestrial, and aquatic.

While we were hiking through the old growth forest in the OESF, we passed a number of dead trees, some sawn in half to defer to the new trail, and some still upright. A few of us stopped to regard these old dead trees, hoping that we would catch a glimpse of an owl. We would also accept a pileated wood-pecker, the evidence of their presence exhibited by this ravaged snag.

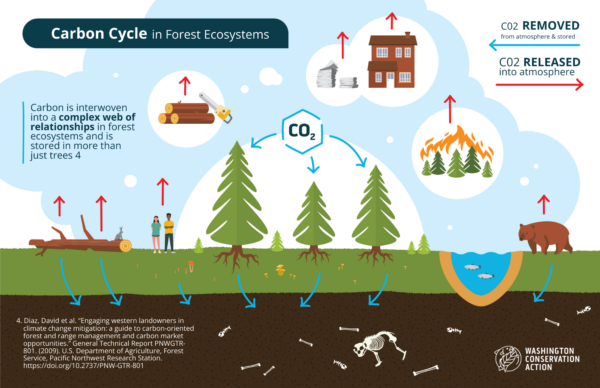

Snags and dead trees play another critical role in the forest beyond roosts for owls or woodpeckers. Trees near water also provide habitat for fish. Through its life span, a tree in a riparian area provides shade and prevents soil-erosion to maintain a healthy watershed. And once a tree dies or is knocked down, logs that fall into rivers and streams provide necessary habitat for salmon, trout, and numerous other fish species. Research in the OESF is beginning to show the stark outcome of improperly logged watersheds.

It should be noted that the old growth forest we hiked through was not representative of the entire Reade Hill trail. Most of the forest was much younger—about thirty years old. It was dark and the trees seemed to hang over us and smothered light; if anything, this was the kind of forest that felt biologically barren. Although it might one day mature into the old growth we had just seen, it would take decades of patience and human restraint.

And the trailhead began at a section of forest in another state of growth entirely. The trail zigzagged through a recent example of “variable retention harvest.”

This type of forest management requires loggers to leave eight trees standing for every acre harvested, as lone sentinels of the forest as it used to be. They are meant to mimic the landscape after a stand-clearing event, such as a forest fire or landslide. However, this was not a natural event—this was human created meant to generate revenue–money that goes to school construction, local county services, and other critical needs for the people of Washington. It is another reminder that for good or ill, humans are part of the ecosystem of the forest, and we can influence whether it thrives as it was meant to by nature, or not.

As second and third growth ages into the ancient forest that was once pervasive, WEC looks forward to seeing how the needs of the community can be met while also maintaining the integrity of the forest ecosystem. The regenerative nature of forests gives us all a second chance to do better this time around. Learn more about the Olympic Experimental State Forest or visit our webpage.