By Ally Arnold, Advocacy and Community Outreach Intern

As a young environmentalist who just graduated college, I am learning what it takes to fight for a sustainable, just future. Unfortunately, the system I was born into is broken. Our American system of government was designed to be changed and molded to meet the needs of the people, and I feel hopeful that change toward a true democracy is possible. My studies of climate change have led me to believe that a transition to sustainable agriculture is necessary, so I have decided to move to the rural Alamosa, Colorado after my internship to learn more about food systems and how to reinvent them for a better future. This blog post is meant to shine light on some of the farmworker struggles in Washington State and why we should invest in solving them.

Overview

Agricultural workers in the U.S. are considered essential during the COVID-19 pandemic, for obvious reasons: we need to eat. The agricultural workers outside the city—the very people providing our sustenance—are our life support. The pandemic has created additional challenges for farmworkers, most of whom are not unionized and are facing difficulties negotiating safe workplace policies. Many seasonal farm jobs that provided much-needed income to Washington farm workers, like the tourism-dependent Tulip farms in Skagit Valley, are not available this year. For the jobs that are available in the fields and packing houses, social distancing measures are difficult to enforce.

In April, Edgar Franks and Marciano Sanchez from Familias Unidas por la Justicia spoke to Washington Environmental Council and Washington Conservation Voters volunteers on a webinar amplifying farmworkers’ calls for increased protections from COVID-19.

Edgar and Marciano shared insights and motivations from their successful negotiations for a historic union contract for farmworkers in 2017.

While Governor Inslee’s administration has responded to calls for farmworker protections during the pandemic, the fight for justice continues: as of May 2020, workers at several Central Washington fruit packing companies are striking. Even if their demands are met, the work of advocating for environmental justice in agriculture continues — along with being built on exploitative and racist labor practices, industrial agriculture is one of America’s largest polluters, and environmentalists need to fight for massive reform. The task is ambitious, but necessary: invest in the agricultural workers who are feeding our nation while transitioning to localized, sustainable food systems.

Background

National Labor Relations Act of 1935

This Act, signed into law by Franklin D. Roosevelt, set guidelines for collective bargaining or actions, such as a labor strike. The act excludes field workers, but includes workers in packing companies. Legislators designed the law in response to violent uprisings like the Colorado Fuel and Iron strike of 1914, hoping it would regulate collective labor forces and prevent violent disputes. The NLRA allows for freedom of association, self-organization, and selection of union representatives who are allowed to negotiate terms and conditions of employment or work protections.

Familias Unidas por la Justicia

In 2017, after three and a half years of hard work, Familias Unidas por la Justicia (FUJ) negotiated a two-year contract with Sakuma Brothers Farm in Skagit County allowing berry pickers to be officially recognized as a union. The collective bargaining agreement increased minimum wages for fruit pickers, declared that seniority would determine hiring/layoff decisions, and established a committee for regular meetings between union representatives and company management. (Read article) Members of FUJ showed up in Yakima this month to help fruit packers negotiate something similar.

May 2020 Strikes at Central Washington Fruit Packing Companies

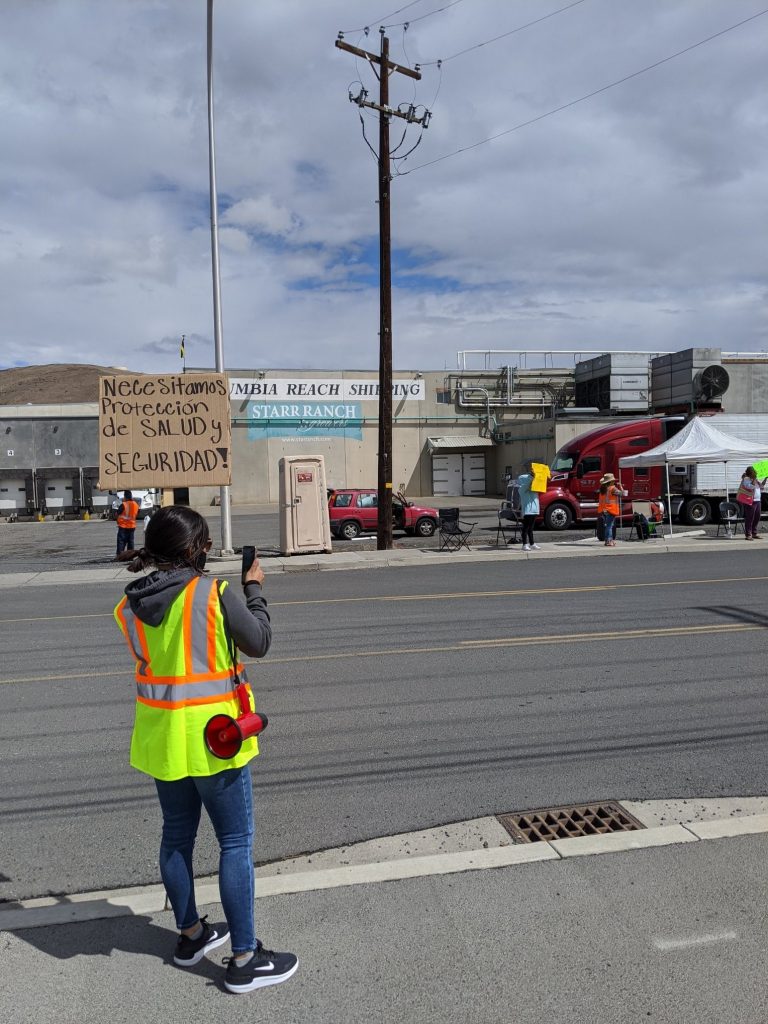

Following outbreaks of COVID-19 at their workplaces, workers at several Central Washington fruit packing companies have walked out of work and are on strike outside their respective workplaces, demanding justice. A few went on hunger strike for 55 hours. While each individual strike has its own company-specific demands, the worker committees formed from the striking workers at each site have many demands in common, ranging from increasing minimum wage and hazard pay to demanding personal protective gear.

Committees formed at each strike site are collaborating to come up with unified demands. The workers are not alone. I interviewed Morgan Michel, one of several volunteers who traveled to Central WA to bring supplies and support to the strikes last week. She witnessed many community members and advocates from across the state standing with the strikers in solidarity (at a safe distance). Volunteers were also able to show support from remote locations; Sunrise Seattle, for example, organized persistent phone calls to the fruit packing companies to encourage negotiations in good faith with workers.

I participated in these phone-calling actions and spoke to several of the fruit packing companies, some of whom seemed annoyed and some empathetic. For volunteers who chose to physically show up in support of the strikes, safety precautions were taken – hand-washing stations were set up, hand sanitizer and gloves were available, most people were wearing masks, and strikers stood at least 6 feet apart.

Are the Strikes Working?

Collective action from strikers supported by Familias Unidas por la Justicia and Community to Community Development Fund, as well as local communities, allies, activist groups like Sunrise Seattle has put enough pressure on the fruit packing companies to begin negotiating and implementing changes. These kinds of collective actions, initiated by the farmworkers themselves, are necessary for creating change in a legislative system that excludes farm workers (an example of this is the NLRA, which intentionally excludes agricultural workers). Edgar Franks noted, “Farmworkers have been on the frontlines of environmental injustice for a long time. But they have also been on the frontlines of organizing and proposing solutions.” Some of the fruit companies are responding to the pressure by increasing pay and providing masks. Nevertheless, the responses have been varied. Some strikers have successfully negotiated with their employers and have seen improvements, while others are still dissatisfied.

Next Steps

There is still more work to be done. Some strikers fear retaliation from their employers, despite being protected by the National Labor Relations Act (since they are not considered field workers). More follow-up needs to be done to ensure that employers do not retaliate against strikers. Furthermore, long-term solutions must be implemented so employees are able to negotiate without resorting to a strike in the future. Structural changes that will allow fruit packers to continue to negotiate in the future, like the FUJ’s two-year contract with Sakuma Brothers Farm, for example, would be a step toward ensuring that workers at the bottom of the food chain (pun intended, but not meant to be condescending) are supported in their essential work. And while FUJ’s union contract is an example of what is possible, it is one of only two contracts of its kind (out of thousands of farms in WA). Edgar Franks explained the reality of the situation:

“Under the union contract, the berry pickers are in a unique position to negotiate working conditions; most other farm workers must work at the whim of their employers, whose major concern is keeping the production going. Even if solutions were implemented, enforcement is a challenge.”

Why Should Environmentalists Support Agricultural Workers in Their Fight for Justice?

Elected officials have a responsibility to ensure that policy and funding solutions protect the communities they represent by holding polluters accountable and safeguarding public health, workers, and the environment. Investing in jobs that can be sustained, such as farming, will be key to ensuring that our economy can thrive without depending on coal, oil, and gas. Currently, however, big agriculture companies in the U.S. rely heavily on fossil fuels, so it is not enough to simply invest in agriculture without implementing systematic changes. As Edgar mentioned in the webinar, “the globalized food system damages the landscape, damages local economies, is labor and resource intensive, and is a recipe for disease transmission.”

Agricultural companies have exploited people of color AND the Earth’s soil in order to feed America. It is time to mend the system.

In order to build both a sustainable and just future, environmental solutions must actively restore the injustices that have occurred in farmworker communities as a result of exploitative use of land for industrial-scale agriculture. According to the USDA Economic Research Service, 57% of farm laborers were Hispanic and of Mexican origin while only 27% of farm supervisors were Hispanic and of Mexican origin; this highlights the racial disparity between supervisors and laborers. Additionally, only 54% of farm laborers in 2018 were recorded as U.S. citizens. Fear of deportation is a legitimate concern for many of these individuals. Furthermore, pesticide exposure, coupled with low wages due to agricultural corporations’ control over the labor force, is one way that intersectional, systematic factors contribute to farmworkers’ impoverished and unhealthy status. Not only is exposure to chemicals linked to higher rates of cancer and illness, but lack of health insurance, crowded housing conditions, and limited sanitation increase the likelihood for farmworkers to contract diseases and decrease their chances of getting proper treatment (Flocks, 2012).

Along with social injustices that accompany large-scale agriculture, heavy pesticide use and fossil-fuel intensive farming practices deplete the soil and produce alarming CO2 emissions. Fossil fuels make modern large-scale agriculture (and the unjust treatment of farm workers that come with it) possible. If we truly start to shift our economy away from oil and gas, jobs will be created, because we will need a larger labor workforce in combination with renewable energy technology to replace the work done by fossil fuels. To be able to pay agricultural workers a fair wage, though, investments in fossil fuels will need to go to laborers instead of the fossil fuel industry. Everyone deserves clean air, convenient transportation, living wage jobs, and communities that are healthy and affordable. To make this vision possible, agricultural workers must be protected and invested in, not only during COVID, but throughout and beyond the just transition away from fossil fuels.

All photos were taken by Morgan Michel.

Joan D. Flocks, The Environmental and Social Injustice of Farmworker Pesticide Exposure, 19 Geo. J. on Poverty L. & Pol’y 255 (2012), available at http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/268

Ally recently completed her B.S. in Ecological, Evolutionary, & Conservation Biology from the University of Washington. While in school, she completed an immersive marine biology program at Friday Harbor Laboratories where she researched kelp crab embryo development in changing pH conditions. She is passionate about grassroots activism, community engagement, and intersections between science and policy. Her goal as an intern at Washington Environmental Council is to learn how to become an effective, strategic, and organized environmental advocate so that she can convince key leaders in non-environmental sectors to prioritize sustainability and environmental justice.