During this time of reckoning with our country’s racist history, it’s important for all of us to look at our own history and understand what role each of us have played in creating and upholding systems of oppression and institutional racism.

Here at the Washington Conservation Action, we are no exception. As a historically white-led environmental organization, we have contributed to the problem through the creation of some of our landmark environmental laws that have led to unintended disparities for communities of color and low-income communities. Today we want to take the opportunity to tell our story of one environmental law that did not consider environmental justice when it was created, how that law exposed racial disparities, and what we are now doing to address those inequities.

The Model Toxics Control Act (MTCA) is responsible for cleaning up sites contaminated with toxic hazardous waste and preventing pollution that poisons our water, land, and communities. MTCA has successfully cleaned up over 7,000 hazardous waste sites throughout the state including large scale sites like Cascade Pole in Olympia—which once leaked toxic waste into Puget Sound—to smaller triumphs, such as the establishment of required clean-up standards for underground tanks at local gas stations.

MTCA’s origin story:

When the federal Superfund law was passed in the 1980s, it became clear that Superfund was only going to tackle the biggest toxic sites such as the Hanford nuclear facility and the Lower Duwamish Waterway, but do nothing for the numerous smaller sites that existed in our state. Recognizing this important gap, the state legislature began working on a state cleanup law.

Washington Conservation Action was instrumental in writing the original bill and defending against an alternative version written by big polluters. Polluting industries influenced legislators to produce a watered-down version that didn’t provide strong enough protections for people or the environment. Separately, Washington Conservation Action and partners had developed a voter initiative and created a groundswell of grassroots support for a strong law. Meanwhile, the legislature passed the version that was less protective and sent it to the voters to decide, along with the more protective version in Initiative 97. Thanks to Washington voters, Initiative 97 passed in 1988 and prevailed as the law of the state instead of the less protective version.

Today MTCA is a cornerstone of our state’s environmental legacy. However, when MTCA was written, no one could have predicted how important this law would be. The original authors thought they were writing a law to tackle a few hundred leaking landfills and wood treatment facilities in rural communities, and believed that all of the sites would be cleaned up in a few years. But as MTCA became established and many more sites were discovered, it became clear that the number of hazardous sites was grossly underestimated. Instead of a few hundred sites, the Department of Ecology found tens of thousands.

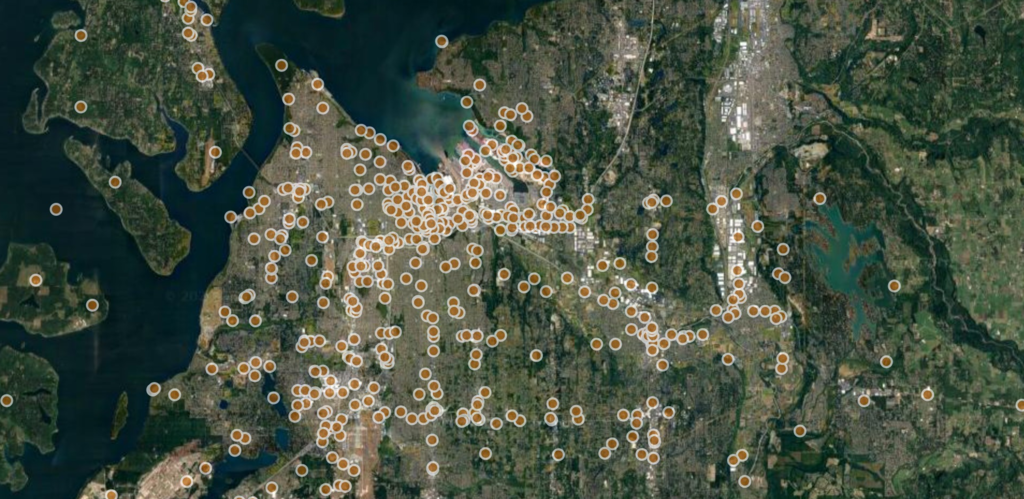

As of today, more than 14,000 MTCA sites have been identified in our state located in both rural and urban areas. To see how many MTCA sites are located in your community, check out the Department of Ecology’s What’s In My Neighborhood tool.

MTCA today: From leaking landfills to environmental justice

For over 30 years, Washington Conservation Action has remained committed to defending and improving the law. From running an initiative in 1988 to developing legislation, working with coalitions, mobilizing grassroots, participating in rulemaking, and defending in the courts, we’ve used nearly every policy tool available to protect and reform MTCA.

In many ways MTCA is considered one of our organization’s greatest success stories. However, MTCA is also an example of how a historically white-led organization created environmental protections for some, but not all. In 2017, Front and Centered, a statewide coalition of organizations and groups rooted in communities of color and people with lower incomes, conducted an equity analysis identifying a disproportionate number of MTCA sites in communities of color and low-income communities – 56 percent of MTCA sites are located in low-income communities and 46 percent are located in communities of color.

MTCA has been successful in cleaning up toxic sites, but these sites are still disproportionately located in communities of color and low-income communities. These communities are not the ones responsible for the contamination, yet they bear the burden of the health, social, and economic impacts.

Washington Conservation Action is committed to centering those most impacted by environmental harms and in this case, that means recognizing the role our organization played in overlooking the disparities, and today we are committed to doing everything we can to fix it. In recent years, we have worked along community partners to equitably reform MTCA. Together we have gone to the legislature to fight for more public participation dollars to provide resources to communities and empower them to lead, stabilized MTCA funding to ensure money is available, and reimagined how MTCA cleanups can bring benefits and goods to the community–such as centrally located affordable housing, community spaces, and more.

MTCA is currently undergoing a ten-year rulemaking process to rewrite the policies and processes guiding the law. The rulemaking process provides an opportunity to address economic and racial disparities by incorporating equity and environmental justice into the rule. Washington Conservation Action sits on the Stakeholder and Tribal Advisory Group and we are using our position to advocate for stronger protections for communities of color and low-income communities.

Right now, WCA Education Fund is striving to increase statewide engagement in the management of MTCA sites, which are disproportionately located in low-income communities and communities of color. Many do not recognize the prevalence of contaminated sites across the state, which undermines one of the tenets of MTCA: engage the public in decision making. Our team is testing multiple techniques for engaging communities in the rulemaking, identifying and partnering with local organizations, and collaborating with Tribes and other groups who experience cumulative impacts.

We still have a long way to go, but understanding our role in institutional racism is an important step in the journey. We learned the harm that can be done by not adequately considering environmental justice in policymaking through MTCA. We believe in protecting, restoring, and sustaining Washington’s environment for all, and we can’t do that without centering environmental justice.