Southern resident orcas and people are linked by patterns of ecosystem and community. Southern resident orcas are matrilineal. They raise their young, pass down unique family songs and vocalizations, and mourn loss. Their struggle to survive tells us human-caused environmental harm has affected the safe passage and spawning of salmon, a source of nourishment not just for orcas but for Washington’s river and coastal Indigenous communities as well. Orcas, people, salmon – we are all moved and affected by one another in life-altering ways. Much like family.

This concept inspired the 15th annual Orca Action Month theme “We are Family”. Originally spearheaded by the Orca Network the month-long campaign is shared by a number of organizations from Orca Salmon Alliance spanning Oregon, Washington and British Columbia, including WEC.

During the action month’s kick-off event in June, Samish elders Rosie Cayou James and Bill Bailey offered blessings and sang in prayer to the orcas of the Salish Sea. Looking out at the water from the shoreline on Lopez Island, James reflected on the kingdom of the orcas and the reciprocity between humans and whales.

“They have gathering villages. They have families to visit,” James said. “They take care of us more than we know. They gather us, they heal us.”

Many Coast Salish Tribes hold orcas with the same love and protection extended to family. Losing an orca is like losing a loved one.

The case of Tokitae (also known as Lolita) is one example of profound loss. One of six orcas captured from Coast Salish seas, Tokitae was sent to be held in a tank at Miami’s Seaquarium in 1970. Lummi Nation, who consider Tokitae a relative, have petitioned for her return to ancestral waters. But the resulting legal battles have been complicated and to this day she remains in Miami. (Read more about Tokitae in this piece by Rena Priest, current Washington State poet laureate and member of the Lummi Nation).

Tokitae’s story is one instance of a pattern where orcas (other marine life, and by extension non-human life) have been objectified for human consumption and entertainment. There are many other stories, including the haunting episode of Tahlequah nearly three years ago who carried the body of her dead calf through the Salish Sea for two weeks in what the world heralded as deep mourning. Talequah’s mourning reminded us of the dire consequences human-made pollution and climate change effects have for the survival of Southern residents. These examples tell us awareness is not enough – action is our only option.

Orca Network launched Orca Awareness Month in 2007 after Orcas were determined to be endangered and listed under the Endangered Species Act in 2005. Orca Network chose the month of June since this is when Southern resident orcas gather in place around the San Juan Islands to feed on the Fraser River Chinook salmon run returning to their natal waters.

In 2007 there were 85 orcas. Now in 2021, 75 remain. A few years ago, Orca Salmon Alliance quickly saw that an effort for awareness and education wasn’t enough and that the campaign’s focus needed to be on concrete action.

There is so much that can be done. Action can happen at the policy level, reducing pollution and toxins in the Sound, and by dismantling infrastructure and policies that have systematically devastated Washington salmon runs. Dams on the Columbia, Klamath and Snake River, among others, have hurt salmon populations and life cycles. They increase water temperatures, create algal blooms, cause fish disease and stunt fish growth. Returning back to spawning grounds is so arduous that many salmon do not survive the trek. This means fewer fish hatch and head to the ocean where they can become food for orcas. Removing dams would affect salmon runs and with more abundant salmon runs, orca’s main source of nourishment would be replenished leading to healthier and better lives.

Fortunately, efforts to restore salmon habitat and salmon runs are underway in the Salish Sea, particularly with the removal of dams in key watersheds.

Last year, dams on the Nooksack River and Pilchuck River were removed to restore the natural flow of the river, opening up important salmon spawning habitat. It will only be a matter of time until the incredible life cycle and resilience of the salmon runs in these two rivers begin to rebound. Additionally, the Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula is a poster child for the ecological restoration and rejuvenation that happens after dam removal.

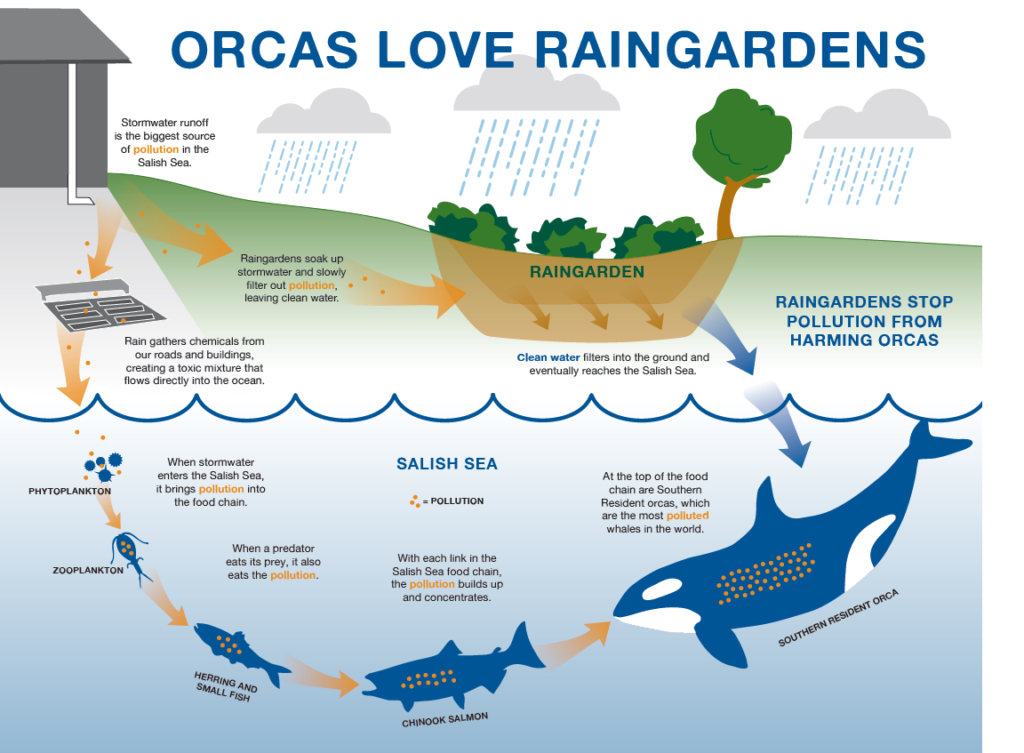

Since stormwater is the top source of pollution in the Puget Sound, toxic runoff negatively affects salmon. The chemicals accumulate in higher concentrations when orca’s consume them. Green infrastructure, including rain gardens, help mitigate the effects of stormwater. Raingardens in particular leverage the natural filtering mechanisms of soil to catch stormwater runoff and filter out toxic impurities before letting water flow into the Puget Sound.

Programs like Orcas Love Raingardens engage Tacoma Public School students and families with rain gardens and green infrastructure as outdoor classrooms to normalize solutions for orca and ecosystem health.

Though the endangered Southern Resident population struggles to overcome the primary threats of food availability, vessel noise and disturbance, and toxic pollution, there is hope. In September 2020, scientists, environmental organizations, and orca lovers celebrated the birth of three new calves, two in the J pod and one in the L pod. Tahlequah, after losing her calf in 2018 gave birth to a healthy male calf. By no means is this a sign that orcas are in the clear, as calf mortality rate is as high as 50% within one year of birth. However this was an uplifting moment for Southern Resident orcas who have struggled to bring in new thriving life into the world.

In 2020, WEC, and several of our coalition partners, were able to push for continued protection of Southern Resident Orcas with a state mandate calling for reduced viewing of the Southern resident orcas by commercial operators.

As of May 2021, all commercial whale watching operators are required to have a license and undergo reporting requirements to operate in the Puget Sound region. Administered by Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the new licensing program:

- establishes seasonal closure of whale-watching on Southern resident orcas from October through June;

- sets a limit of three whale watching operators at a time with a group of Southern residents within ½ nautical mile;

- sets time limits for daily viewing;

- formalizes the ‘no-go’ zone on the west side of San Juan Island;

- prohibits viewing groups of orca with young calves or those designated sick or vulnerable.

These mandates are all to ensure the well-being and safety of Southern residents.

Lasting change for our Southern resident orca neighbors calls on all of us to act. For organizations like WEC, that means working alongside partners on policies that will restore Chinook salmon runs, make the Salish Sea quieter and reduce vessel disturbance, and prevent toxic pollution. It also means honoring Tribal treaty rights and following the leadership of Tribal Nations to restore salmon runs and remedy broken ecological relationships and lifeways.