Rhys Coffee, Evergreen Forests Program Intern

WEC’s third annual Carbon Friendly Forestry Conference brought together a diverse group of thinkers – policymakers, academics, landowners, tribes, conservationists, and business owners – to discuss sustainable forest management practices and natural climate solutions.

Being new to forestry and sustainable forest practices, I was excited to listen to and engage with so many different perspectives. Before my internship at WEC, I had limited exposure to topics like carbon sequestration and natural climate solutions in my undergraduate studies.

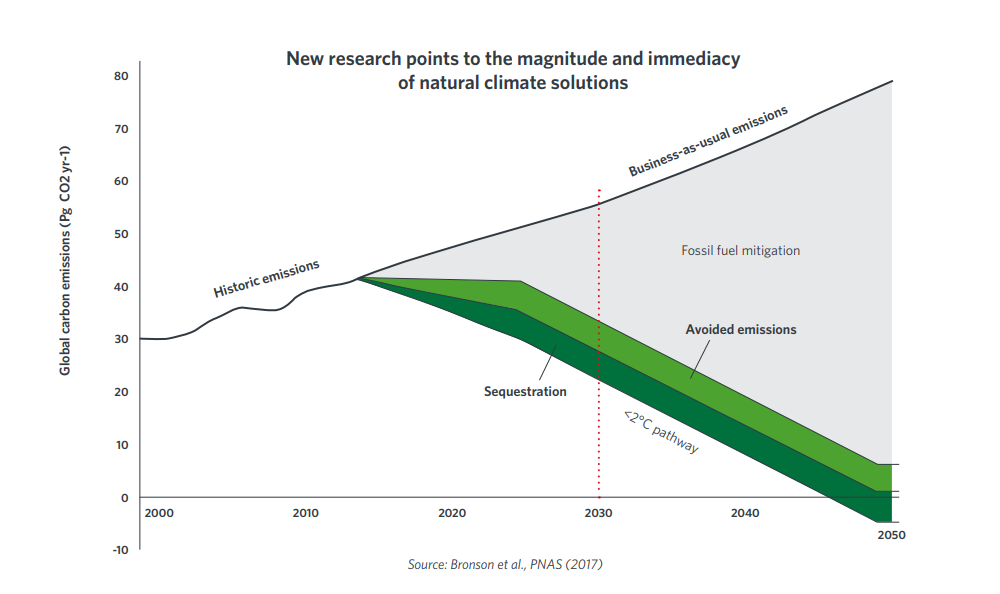

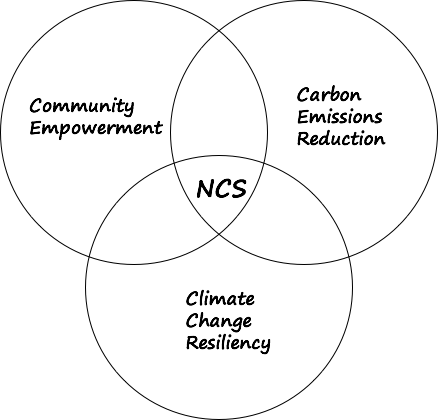

Natural climate solutions (NCS) are methods of sequestering carbon and avoiding future greenhouse gas emissions through improved land management, conservation, and restoration of various ecosystems. NCS not only sequester carbon, but provide additional ecosystem services such as improved soil quality, air filtration, flood control, flood protection, improved water quality, enhanced biodiversity, and increased climate resilience. The most exciting part of natural climate solutions is the significant impact they could have on climate change mitigation. It is estimated that over 1/3 of the CO2 reductions needed by 2030 to keep the global average temperature from rising 2°C can be fulfilled through natural climate solutions.

The day started off with a passionate speech from Hilary Franz, Commissioner of Public Lands, who referenced an experience she had the prior summer. Commissioner Franz reminisced about the time she spent in the forests of the Columbia River Gorge as a child, and how she longed to take her own children there one day. On a road trip with her family in 2016, she was passing through the area and considered stopping, but was pressed for time and figured she would just come back the next year. In the summer of 2017, over 50,000 acres of forest were burned over a span of three months in the destructive Eagle Creek Fire. Commissioner Franz highlighted that we are already feeling the effects of climate change and stressed that we must take action to make our lands more resilient and invest in carbon sequestration and clean energy to protect future generations from the climate disaster we are facing.

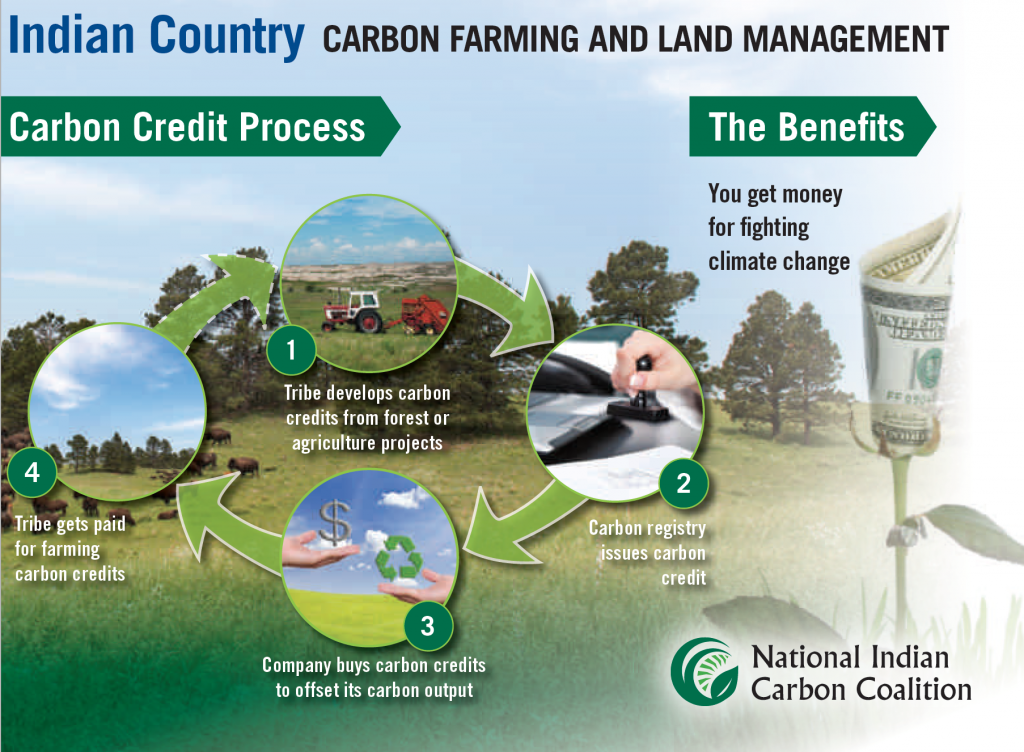

The next speaker was Byan Van Stippen, the program director for the National Indian Carbon Coalition and member of the Oneida Nation. The National Indian Carbon Coalition is a nonprofit that helps tribal landowners and tribal nations manage their lands for carbon farming projects. Stippen talked about the re-framing of climate change as an economic opportunity to tribes. I had never thought of climate change in this way and was intrigued and impressed by Stippen’s presentation. Carbon farming allows tribes to enter into a carbon market by sustainably managing their land and doing things like habitat restoration, conserving grassland, and reducing CO2 outputs from power plants. Carbon farming for tribal landowners generates revenue, promotes land stewardship, preserves tribal ownership, and improves ecosystem services of the land. Currently, the three projects NICC is working on are expected to generate an estimated 17 million dollars from carbon credit sales.

In the afternoon, the conference was structured into breakout sessions. I chose to attend a presentation about city carbon credits given by Liz Johnston. Johnston works for City Forest Credits, a nonprofit organization that proves a framework for companies to invest in local carbon projects. These projects have a large geographic spread; from riparian reforestation in Austin, Texas, restoration of a historic cemetery in Richmond, Virginia, to the protection of land at Soaring River Park in King County. Urban forests have been historically been left out of the equation when it comes to carbon credits, but City Forest Credits creates an opportunity to recognize their value for addressing climate change. I thought this presentation was extremely interesting and relevant because of the large amounts of people these projects impact: nearly 80% of the population of the U.S. lives in cities and towns, and this number continues to grow. Planting and restoring trees in urban areas reduces temperatures (urban heat island effect), improves air quality, reduces stormwater impacts, and provides space for communities to gather and recreate.

Throughout the conference, I was continually impressed by the innovative approaches to natual climate solutions that organizations are taking. One commonality I noticed in these solutions is the level of involvement and benefits they provided for communities. In the closing panel of the conference, Darcy Nonemacher, WEC’s Government Affairs Director, said something that really stuck with me:

“Natural climate solutions let everyone see themselves as part of the solution.”

Climate change can be so overwhelming and intimidating and many times we find ourselves asking “what can I do?” Natural climate solutions provide answers to that question. In our own lives we can do a better job at promoting natural climate solutions through actions like voting for elected officials who support NCS, volunteering to plant trees, participating in community restoration initiatives, or even making sure the paper and wood products we purchase are FSC certified. NCS simultaneously addresses the climate crisis by sequestering carbon and increasing climate change resilience and creates a space for community empowerment.

Before attending the Carbon Conference, I knew very little about the carbon sequestration potential of Washington’s private and public lands. Carbon sequestration wasn’t on my radar as an effective way to mitigate climate change; the popular narrative of reusable shopping bags and to-go mugs is featured more in mainstream culture than habitat restoration, sustainably sourced wood products, and planting city trees. Reflecting on the knowledge I gained from attending the conference gave me a new perspective, as to how as an individual I can take action in the current climate crisis.

Rhys Coffee

2019 Evergreen Forests Program Intern

Rhys was raised in Juneau, Alaska where she cultivated a deep love for the outdoors and a passion for protecting the environment. She graduated from the University of Portland with a degree in Environmental Science, and while there helped found an eco-friendly clothing company called Branching Threads. Before moving to Seattle, Rhys worked in her hometown as an environmental technician at an environmental consulting company. During her time there she collected water samples and performed analyses to help uphold the Department of Environmental Conservation’s Alaska’s water quality standards for wastewater treatment on cruise ships, ferries, and land-based establishments. In her free time, Rhys enjoys knitting mittens, hiking, and skiing.