Driving on Interstate 90, one can get a real sense of the majesty and diversity of the Pacific Northwest’s forests. Woven between the trees are intricate ecological systems vital to the health of Washington’s communities and ecosystems. Forests clean our air, filter sediment and pollutants from our water, prevent flooding and landslides, absorb and store carbon, and are places of cultural importance. They provide us with food, jobs, wildlife habitat, wood products, and recreation opportunities.

Since Washington Environmental Council’s founding in the 1960s, we have advocated for conservation of Washington’s natural forests and the sustainable management of working forests that provide products like timber. Over these years, we have learned from scientists, communities, and Tribal leaders that not all forest management is equal. Management practices that maximize revenue and timber above all other benefits degrade the natural ecosystem processes that provide us with clean air, water, habitat, climate mitigation, and more. The details of forest management practices have real impacts on the lives of Washingtonians. We rely on forest products like wood and paper to build our homes, care for our families, and enrich our lives—but to keep our state and planet safe and healthy amidst a climate crisis, we need these products to originate from working forests that are stewarded to enhance ecological health.

A recent article in The Seattle Times, “Amid climate crisis, a proposal to save Washington state forests for carbon storage, not logging” presented many different perspectives in a complex and important dialogue about managing Washington’s forestlands not only to respond to today’s reality, but also to provide for future generations. This raises the question: how do we address climate change and support local economies, communities, and forests?

This question guides the work of WEC’s Forest Program.

WEC does not believe it is necessary to cease all timber harvests on state-managed forestlands to address the climate crisis. This is one approach, but not the only approach. We can meet the complex needs of our communities and ecosystems for generations to come by taking a more holistic, ecologically-based approach to forest management. To ensure changes in forest management are successful and just, we must also take complementary actions to ensure the economic health and resiliency of communities that rely on forestry jobs and revenue.

how do we address climate change and support local economies, communities, and forests?

The Forests of the Pacific Northwest are Part of a Climate Change Solution

Forests are central to the Pacific Northwest’s identity. Locally, forests clean the air, filter the water, and provide communities with employment, revenue, cultural significance, recreational opportunities, and more. Globally, the forests of the Pacific Northwest are also significant: they are among the most carbon-dense forests in the world.

Forests absorb carbon from the atmosphere and store it in trees, soil, fungi, and other vegetation—a process known as carbon sequestration. When coupled with significant emissions reductions, forests are an invaluable tool in the fight against the climate crisis. Natural climate solutions focused on avoiding deforestation and improving forest management can even provide 18% of the climate change mitigation needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C. According to a study from Oregon State University, the Pacific Coast and Cascade Mountain forests of Washington and Oregon are the highest priority area for forest carbon sequestration in the contiguous western United States.

The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) manages over 2 million acres of forest in this carbon rich region: the state trust lands managed on behalf of the people of Washington. State trust lands are publicly managed lands that generate revenue for specific beneficiaries, including public universities, the K-12 school construction account, and certain counties and junior taxing districts. DNR currently manages these working forestlands in a way that prioritizes maximizing revenue from timber harvests. 1.4 million acres of DNR-managed forests are located west of the Cascade crest, which is a high priority area for carbon sequestration given the productivity of trees in this region. DNR must lead on harnessing Washington’s remarkable forests to mitigate the climate crisis, and do so in a way that balances carbon sequestration with the many other benefits that forests provide.

State Trust Management Must Reflect Today’s Reality

The system governing state trust lands was created upon Washington’s statehood in 1889, in a very different world. 131 years later, we are in a climate and a biodiversity crisis, with a state population almost 22 times that at statehood. Today’s reality of rapidly changing environmental, economic, and social needs exerts more pressure on our forests, and demands that we evolve management of the state’s forestlands to better support multiple benefits.

Timber harvesting is a critical source of revenue for some of the state’s trust beneficiaries—rural counties in particular, which dedicate these funds to critical services. We must work to ensure these counties receive reliable funding. At the same time, this revenue is no longer a significant part of the budgets of other beneficiaries such as the K-12 school construction account and some major universities. There is ample opportunity to reshape the state trust land management system to address the needs of today, including those of rural communities.

The economy and natural resource protection are too often positioned in opposition to each other, and Washington’s state trust lands are no exception. We reject this false dichotomy. Washingtonians should not be forced to choose between timber harvests for revenue and healthy forests that protect local air, water, and habitat. Although tradeoffs do exist in some forest management decisions, there are many management strategies that can improve outcomes for both climate and people.

As the climate crisis threatens the future of our forest ecosystems and human health, it is more urgent than ever to manage in a way that balances the long-term benefits forests provide. In doing so, we can create collective, long-term solutions to meet economic and environmental needs. WEC is committed to working with beneficiaries, the legislature, and the Department of Natural Resources to find these solutions.

In our current work, WEC’s Forest Program is advancing this effort through several avenues:

- Clarifying DNR’s responsibility to manage state trust lands for multiple values,

- Advocating for a carbon policy framework to guide management of forested state trust lands for climate change mitigation and adaptation,

- Promoting ecological management of state-managed forests, including retaining rare old forests, and allowing trees to grow older before harvest,

- Supporting the development of incentives for landowners to use ecologically-based, climate-smart management practices and to conserve both working and natural forests.

Clarifying DNR’s Mandate to Manage Forests for Multiple Benefits

To gain clarity on DNR’s authority and flexibility to manage forests for a diversity of values beyond only economic return, Conservation Northwest, WEC, Olympic Forest Coalition, and local individuals have brought forth a lawsuit urging the courts to interpret the language in the state constitution stating that public state lands are held in trust “for all the people.”

WEC believes the constitutional language “for all the people” requires management of these lands in the long-term best interest of all Washingtonians, rather than prioritizing revenue generation above all other forest benefits and services. This historic case could lay the groundwork for re-imagining the way state forestlands are managed.

Clarity on the law is particularly important now, as the climate crisis threatens the health and longevity of all the benefits Washington’s forests provide, including clean air, clean water, carbon sequestration, flooding and landslide prevention, and timber revenue. Last month, the case was granted direct review by the State Supreme Court. You can read more about the case here.

A Carbon Policy to Guide Climate Change Mitigation & Resilience on State Forestlands

As demonstrated by the Seattle Times article, the role of state-managed forestlands in combating climate change is part of the public discourse now more than ever—and time is of the essence in the fight against the climate crisis. Natural resource management must increase carbon sequestration and climate resilience.

DNR currently has no policy to incorporate climate mitigation or carbon sequestration into forest management decisions. The recent Washington Forest Ecosystem Carbon Inventory conducted by DNR and USFS underscores the need for a policy to guide carbon management. The results of the study suggest that, when we account for both carbon emitted and sequestered, forests across the entire state of Washington sequester a net amount of carbon equivalent to approximately 16% of the state’s annual greenhouse gas emissions. However, the annual net carbon sequestration on DNR-managed lands is not significantly different from zero. In these times, the agency can and must do better.

DNR currently has no policy to incorporate climate mitigation or carbon sequestration into forest management decisions.

So in June 2019, Washington Environmental Council, Washington Conservation Voters, and the Washington Forest Law Center submitted a formal request to the Board of Natural Resources (which establishes policies for DNR) asking for the development of a carbon policy to guide the management of forested state trust lands.

A carbon policy would provide a framework for DNR to increase carbon sequestration and climate resilience along with—not instead of—other management objectives. Such a policy would help DNR balance many values in forest management decisions, and better reflect the climate realities of today and tomorrow. Our request for the creation of a carbon policy remains unfulfilled two years later.

Older Trees & Ecological Management to Support Environmental & Economic Outcomes

One of the most straightforward, impactful strategies to improve environmental and economic outcomes in working forests is simply to grow trees for longer.

Older, bigger trees are particularly effective at sequestering carbon and providing a multitude of other benefits, including wildfire resilience and a potential increase in sustainable timber volume over the long-term. Unfortunately, current timber harvests often occur when trees are young, in order to optimize short-term revenue—long before trees have reached their maximum growth and ecological potential.

Allowing trees to grow older by extending the amount of time between harvests is central to answering the question of how we address climate change while supporting local economies, people, and forests.

A strategy of shifting to longer rotation lengths, coupled with managing forests in a way that mimics natural ecosystem functions and disturbances (practices carried out by Indigenous peoples for generations) can store more carbon, safeguard water quality and quantity, prevent flooding and landslides, and provide ongoing forest sector employment and revenue important to Washington’s rural communities. Such ecologically-based management strategies deliver a broader range of forest benefits and are better suited for the world we live in today, rather than the intensively-harvested industrial forests across much of Washington’s forest landscape.

As we continue to innovate towards the goal of managing productive forests for multiple benefits, we must also recognize where timber harvesting should not occur. It is critical that we conserve the remaining older, structurally unique forests on state land. DNR has a commitment to work toward developing older forest structures on 10 to 15 percent of the lands in many Western Washington planning units over several decades, which they have not yet achieved. Timber sales like the Smuggler sale, described in the Times article, should be carefully examined to determine how they contribute to DNR goals and safeguard biodiversity. The responsibility to identify and protect old and structurally unique forests should not fall to the public—this work is entrusted to DNR and to lawmakers. We look forward to hearing how the agency will meet their current commitments to conserving old and unique forests.

Financial Incentives for Ecological Forest Management

We need to maintain healthy, working forests, so they can continue providing countless vital benefits to Washington’s communities and ecosystems. Doing so requires appropriately valuing forests and the ecosystem services they provide.

Financial incentives can enable landowners who rely on revenue from timber harvests to transition from industrial practices to more holistic, ecological management. Whether on public land or private land, we must think creatively about how to compensate landowners for maintaining standing forests, restoring forest ecosystems, and improving forest management practices. Landowners could receive incentives for the carbon sequestration on their forestland, for transitioning to extended rotation lengths, or for conservation of old and structurally unique forests, to name a few strategies. Such financial incentives would allow us to tap into the broader suite of public benefits offered by forests while economically strengthening the rural communities who rely on them. WEC is ready to help scale-up and develop new financial incentives that support transitions to more ecological forest management.

If rural communities and trust beneficiaries receive reliable financial compensation for conserving and managing forests ecologically—rather than only receiving compensation for logging—dedicating land to ecological forest management and carbon sequestration could become a reality for rural communities. This could create a win-win scenario for people and the climate.

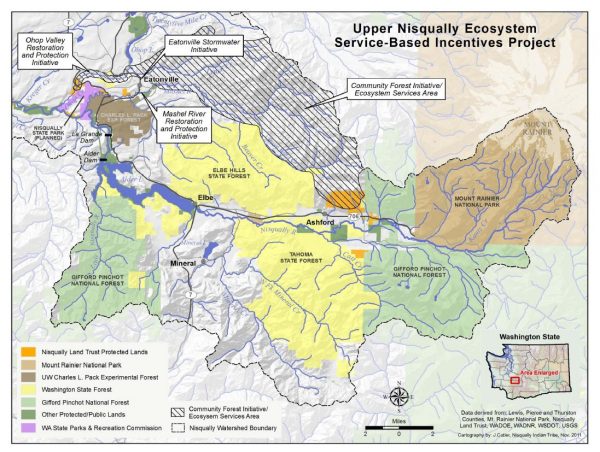

WEC works to support development of financial incentives through a variety of mechanisms, including advocating for funding for community forests, growing demand for climate-smart wood from ecologically-managed forests, and developing projects like the Nisqually Carbon Project.

The Path Forward

The climate crisis is accelerating, and we need new solutions and a re-evaluation of our traditional ways of operating. We need to change the way we approach valuation and management of working forests—and that means viewing forests not only as a source of timber, but also a source of ecosystem services, cultural value, recreational value, and driver of climate change mitigation and adaptation.

For too long, we have optimized forests for timber production. Forests can be part of the solution to our local and global challenges, and we believe Washington can lead the way on our state’s public lands. WEC is committed to working with the Department of Natural Resources, tribal nations, local communities, and industry to ensure a healthy future for our state forests and all of us who depend on them for generations to come.

Learn more about our work on state-managed forestlands

WEC and WCV publish an annual State of our Forests and Public Lands report highlighting the progress of the Commissioner of Public Lands and the Department of Natural Resources—see the report here